At one time there stood a monument in front of the old Parker Center dedicated to all Los Angeles Police Officers who have made the ultimate sacrifice. It is a timeless granite tribute to the men and women who have given their lives in the line of duty. In May of 2014, the LAPD, working with city officials, erected street signs to honor the memories of each officer killed in the line of duty. Currently, 206 personalized signs denote the areas where each officer was killed. Unfortunately, one was missed.

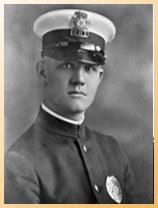

In doing research for my new book, The Protectors: A Photographic History of Police Departments in the United States, I came across the annual report from the LAPD to the mayor, dated from 1917. Inside, toward the back of the thick book, was a section labeled: “Killed on Duty.” Under the headline were five names, one of which was that of Officer C. H. Crow. It reads:

“June 17, 1916, Patrolman Crow, detailed to duty in the Detective Bureau, in the investigation of a felony case, followed the suspects into a desert portion of Imperial County. Without water, and in the intense heat he suffered a sunstroke, but followed his man and arrested him. The following day he died.”

This information led me to one of the newspapers of the day, were I found one small article. The headline read: “Officer Follows Duties to Grave.” Just a week earlier, there had been a felony theft of $1,000 (which today would be about $21,000) worth of clothing from the store of Mr. Morris Cohen. Led by information provided by Mr. Cohen, Patrolman Crow and his partner, R. L. Shy, were told that there were two suspects who had fled to San Diego. Without delay, the two officers departed. Arriving in San Diego, the patrolmen, who were on loan to detectives, and Mr. Cohen were told that the two suspects were in Calexico, a very remote city located at the Mexican border in the Imperial Valley Desert, 90 miles east of San Diego.

With temperatures well over 100 degrees and, according to the newspaper, reaching 135 degrees, the trio set off for Calexico. One must realize that in 1916 the roads were predominantly dirt, with no civilization or amenities along the route. By the time they reached Calexico, Mr. Cohen was near collapse and was immediately sent back home. Patrolman Crow was also extremely ill from the sun but insisted to his partner that they should not give up. They continued their pursuit without water or provisions.

After receiving information that the suspects had fled to Mexicali, Mexico, but “were hovering” between the two cities, the officers staked out the border area. With temperatures again soaring, the two officers, ill-prepared for the extremes of the desert, suffered stifling heat but would not give up. Their patience paid off when the two suspects were seen crossing the border back into the United States and were promptly taken into custody.

Less than an hour after the arrest, and with the suspects safely put away, Patrolman Crow collapsed. His partner quickly drove him to the hospital in Calexico. When word reached the LAPD, Assistant Chief Home telegraphed that “no expense should be spared in fighting for the officer’s life.” But, according to the physicians, there was little hope of his surviving even a few hours. Officer Crow died a short time later from exposure to the elements.

The funeral service took place at Christ’s Episcopal Church and was attended by hundreds of friends. All the men who knew Patrolman Crow were granted time off to attend. As the police band played “the requiem,” attention was drawn to the back section of the church, where a disheveled man could be heard sobbing. It was later discovered that inebriated man was Danny O’Lalley, who adored “Pat” Crow (as he was known).

Until five years before, O’Lalley was a drunkard. Danny would work three days and then spend all his earnings at a bar. Then one night he had a run-in with Patrolman Crow, who was working a foot beat in the area. Crow took the inebriated man aside and explained how he could change his life around. Danny never forgot that “sermon,” and that night promptly turned over $47 he had in his pockets for safe keeping, but mostly so he would not squander it in bars.

The following night when again Patrolman Crow spotted O’Lalley, he was surprised to see him sober. Feeling encouraged, Crow returned the money to Danny, who proclaimed Crow was his best friend. From that point on, whenever Danny had the urge to spend his money at the bars, he would track down Crow and turn over most of his money for safekeeping. He told Pat that he wanted his friend to think he was a “proper” man. O’Lalley became a changed person.

Years later when he heard of the death of his dearest friend, Danny O’Lalley was at the church. Talking to no one in particular, Danny proclaimed, “Pat would let me get drunk when I felt so bad, so I took what I wanted.” As he quietly cried in the back of the church, he muttered, “I don’t think Pat would care if I got a little overdone today. He knew me and kept me straight for five years.”

That is the type of man Patrolman Charles “Pat” Crow was. He lived his life helping those in need and, when chasing down two wanted felons, knowing he was in deep trouble from the heat, pushed through and arrested the thieves. Perhaps Pat can better rest knowing the LAPD family never forgets a brother or sister officer killed in the line of duty. Rest in peace, Officer Crow. You are missed but not forgotten.

Postscript: At the time of this writing, the Department is doing its due-diligence to determine if Patrolman Crow’s name should be listed to the Officers Killed in the Line of Duty records. I for one believe without a doubt he should be. Why he was not listed in his time, no one knows. If you have any feelings on this subject, please let me know and I will pass it along to the Department: policehistoryjamesbultema@gmail.com.

![chief_beck[1]](https://guardiansofangels.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/chief_beck1.jpg?w=104&h=148)