Los Angeles in 1930 was a society gone wrong. The Great Depression was in full swing, putting a death grip on the entire country. Many Americans depended on the government to feed them, and long bread lines weaved their way through the streets of the nation. The Dust Bowl winds blew many to California and into Los Angeles. With unemployment rates at 20 percent, businesses closing and no work to be found, many turned to crime. However, some, such as Joe Luby, had been career criminals even during the good times. The ex-con was wanted in Detroit for a double homicide committed during a robbery. Avoiding the law in Michigan, Luby was in LA checking out banks—his specialty.

Near the intersection of Hollywood Boulevard. and Normandie Avenue, was the Security-First National Trust and Savings Bank. During the 1930s, it was the practice for banks to close for an hour at lunch. Security-First was no exception. The bank manager, Mr. W.H. Garland, and four tellers were just getting ready to enjoy a peaceful lunch—or so they thought, when Luby, aware of bank practices, walked in. The harden criminal “coolly” approached Mr. Garland, pulled a revolver and demanded cash. With the gun pointed at his chest, Garland walked over to the teller cash drawer and nervously fumbled to pull out $500 in bills ($4,400 in today’s money). With the cash lining his pockets, Luby slowly backed out of the bank with his gun swinging back and forth keeping everyone in their seats. As he reached the door he whirled and jumped into his car. Garland quickly sounded the bank siren.

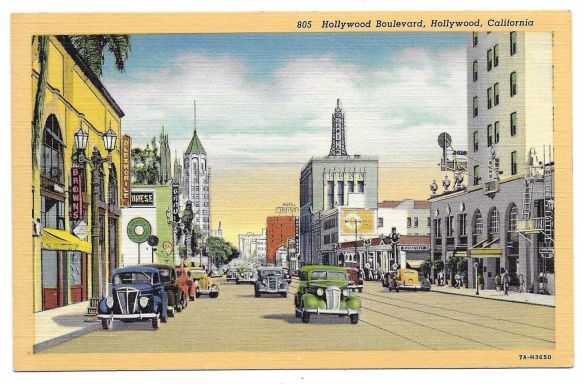

Hollywood Boulevard, circa 1930s

Sitting in his personal car not more than 100 feet from the bank was Los Angeles Police Sgt. A.A. Campbell. Looking up when he heard the deafening siren of the bank, he saw a man run out and jump into a roadster. Campbell quickly grabbed his revolver and ran directly toward the man as he got into his stolen car. As Campbell approached, the suspect fired several rounds, which the sergeant would later recall “went screaming past his head.” Campbell fired three quick shots back at Luby, who slumped forward in his seat. Campbell was confident he’d got him. But no sooner had this thought appeared than Luby jammed the car into gear and roared off.

Sergeant Z.Y. Gruey happened by in his car at the exact time that Luby took off. Campbell jumped into Gruey’s car, and they squealed off after Luby. The two sergeants followed Luby north on Normandie and then east on Franklin but soon lost him in traffic. As they searched for Luby, Gruey pulled up to a call box and let Hollywood station know what was going on. According to Campbell, “Then we picked up Officer E.G. Brown and thinking the suspect had driven toward the hills, we drove north on Catalina street.”

Traveling just a short distance, the trio of LAPD officers caught sight of Luby driving just in front of them. As they were catching up to him, the armed robber slammed on his brakes and jumped out of his car, tumbling down the side of a bushy ravine. Campbell picks up the story: “Just before he vanished over the brow of the hill, he whirled about and fired several times. Both Brown and myself answered the fire.”

The three officers went in foot pursuit. The men could hear the suspect crashing through the thick brush, and as if in some arcade game, they shot at Luby every time he reached a clearing. As the suspect reached the bottom of the gully, Campbell and Gruey ran back to the car, believing they could drive down, and around, and head Luby off from the far side of the ravine. They left Brown behind to put pressure on the suspect. As they drove off, they heard more shots being exchanged. As the two officers glanced over their shoulders, they saw Luby duck behind a house.

A few minutes later, Luby was driving off in a small truck that he had stolen at gunpoint from a local Japanese gardener. The suspect headed to Vermont Avenue. Meanwhile, the two sergeants had reached the bottom of the hill and were driving along Los Feliz Boulevard when they spotted their man “careening down” Vermont. Reaching the intersection of Vermont and Los Feliz, the suspect smashed into a parked truck. Campbell said, “We drove up alongside, and I held my gun on him. He cried out: ‘I give up. Don’t shoot. I quit.’ But as I was within a few feet of his car, he suddenly pointed his gun directly at me. Before he could pull the trigger, I let him have it.” This time when Luby slumped over; it was for real, he was dead.

Luby’s rap sheet was long and violent. In 1920 he had been arrested by LAPD for robbery, which was reduced to vagrancy. In 1921 he was sent from Chicago to the Illinois Reformatory for 10 years to life. In 1926 he was arrested in Chicago for grand larceny. In 1929 he was arrested again in Chicago for robbery. Bail was set at $7,500, which Luby jumped. In February of 1930, Detroit police announced a reward of $500 for Luby’s capture on the charge of the murders of two special agents of the Western Union Telegraph Company during a robbery at which time he also wounded a Detroit policeman.

Two weeks after the bank robbery, the three brave officers received checks for $500 as a donation from the Security-First Bank. Assistant Chief of Police Finlinson proudly presented the checks in a ceremony given for the officers “for their valor in chasing and slaying a bank bandit at the climax of a spectacular running gun battle.”

My website: policehistorybyjamesbultema.com